Old Categories, New Territories, and Future Directions: A Response to Bernard Lightman

By Peter Harrison

A note from the editor: In a previous article on this site, historian of science Bernard Lightman offered a reflection on the new work of Peter Harrison. Harrison’s book, The Territories of Science and Religion, seeks to outline how conceptions of science and religion have changed throughout history, and details the inadequacy of projecting our present categories onto the past. In his reflection, Lightman raised four points about Harrison’s work: concerning the influence of Darwin’s evolution, the role of ‘professionalization’, the impact of evolution on natural theology, and how Harrison’s Territories relates to the ‘complexity thesis’, the current dominant idea in the historiography of science and religion. Below is Harrison’s response to Lightman’s post:

I’m grateful to Bernie Lightman for his thoughtful and perceptive comments on The Territories of Science and Religion. Lightman is a leading authority on science and religion in the nineteenth century, and a scholar from whom I have learned a great deal. Accordingly, I was interested to see his assessment of my treatment of a pivotal period in which he has a particular expertise. Fortunately, it seems mostly to have passed muster, although Lightman has issued a few challenges and identified some important issues that warrant further attention.

Here, then, are the matters to be explored. First, what was the significance of the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species for nineteenth-century discussions of science and religion? Second, is ‘professionalization’ the right way to characterise new understandings of the status of natural science in nineteenth-century Britain? Third, did the rise of evolutionary thinking in the nineteenth-century bring about the demise of natural theology? Fourth, what contribution does the book make to the historiography of science and religion, and how does it relate to the field’s regnant ‘complexity model’ outlined in John Hedley Brooke’s landmark work, Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives (1991).

On the first point, Lightman draws attention to the fact that Darwin seems to receive scant attention in my chapter on the nineteenth century. This case of ‘Darwin deleted’ (if I may borrow the title of Peter Bowler’s recent book), looks like a significant oversight in a book concerned with science and religion. An omission such as this certainly does require an explanation, and it amounts to offering a qualified ‘no’ to Lightman’s question: ‘Was there a Darwinian revolution?’[1]

It is important at the outset to distinguish evolution, a theory about gradual biological change over time, from natural selection, which is a specific mechanism of evolutionary change. Evolutionary thinking had long predated Darwin and there is an important sense in which the Origin of Species (1859) was pivotal only because it was the culmination of a succession of evolutionary writings. To mention just two of these, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck had published a systematic theory of evolution in the first decades of the nineteenth century, while in 1844 the Scottish publisher Robert Chambers had produced a best-selling work on biological and cosmic evolution, Vestiges of the Natural History of the Creation. In this context, Darwin’s work was important not simply because it proposed a theory of evolution, but because it marshalled a remarkable body of evidence in support of the theory and managed to dispel the lingering doubts of a number of leading thinkers about the scientific status of evolution.

Caricature by André Gill of Charles Darwin and Émile Littré depicted as performing monkeys at a circus breaking through gullibility (credulité), superstitions, errors, and ignorance.

Ironically, though, this acceptance of evolution came at the cost of what we now regard as Darwin’s singular contribution—the mechanism of natural selection. This sidelining of natural selection made it possible for a number of Darwin’s contemporaries to embrace evolution as a teleological and progressive process that culminated in the appearance of human beings. For Darwin’s religious supporters—and there were many more of these than is often acknowledged—evolution could be squared relatively easily with both the uniqueness of human beings and God’s providential guidance of the evolutionary process. On the other side, even close allies of Darwin such as T. H. Huxley who, it must be said, was not over-friendly to religion, never fully embraced the mechanism of natural selection. In spite of this, as Lightman rightly suggests, Huxley was able to seize upon elements of the controversy generated by the Origin to serve his own project of promoting science over theology, and of liberating science from clerical interest and interference.

It is significant, then, that T. H. Huxley’s grandson, Julian Huxley, was later to describe the period between the publication of the Origin and the 1930s not as a ‘Darwinian revolution’, but as the ‘Eclipse of Darwinism’. As Lightman has himself shown, this period was dominated by philosophical and progressivist forms of evolutionary theory, typified by the thought of Herbert Spencer. Only in the third decade of the twentieth century do we witness the emergence of the modern evolutionary synthesis which provided a genetic account of natural selection. As Peter Bowler reminds us in the previously mentioned Darwin Deleted: Imagining a World without Darwin (2013), it is important not to interpret Darwin’s nineteenth-century impact in the light of post-1930’s developments in evolutionary science.

In sum, the place of Darwin in nineteenth-century science-and-religion issues has typically been overstated because the initial impact of Darwinism has been routinely read in the light of subsequent twentieth-century developments. The latter include not just the modern evolutionary synthesis, but also reactionary religious movements such as young earth creationism. For all that, Lightman is correct to point out that readers would come to the book with a reasonable expectation that there would be more discussion of Darwin, and if nothing else, an explanation for his low profile in the book is in order.

The second issue that Lightman raises is to do with my use of the term ‘professionalization’ to characterise developments in science in late nineteenth-century Britain. Briefly, I agree that the term is problematic, and can only plead in my defence an overfondness for Frank M. Turner’s classic paper: ‘The Victorian Conflict between Science and Religion: A Professional Dimension’.[2] What I meant to convey in this section of the book was that there was at this time an explicit attempt to find a distinctive persona or identity for practitioners of the natural sciences. This was part of a process of social differentiation that was integral to the emergence of our modern and secular understanding of science. My argument is that this new identity—the scientist—could be constructed in such a way as to suggest its incompatibility with a religious mindset. As Francis Galton forthrightly expressed it in his English Men of Science (1874), ‘the pursuit of science is uncongenial to the priestly character.’ Science-religion conflict could thereafter be understood not only in terms of supposedly conflicting doctrines, but also in terms of the putatively incompatible personae of those who ‘professed,’ respectively, science and religion. We hear echoes of this in contemporary polemics that set up a science-religion conflict in terms of a religious mindset based on faith that must necessarily be opposed to a scientific mindset grounded in reason.[3]

Lightman’s third concern is to do with whether I have overlooked the resilience of natural theology in the post-Darwinian period. Quite possibly, I have, albeit inadvertently. In light of my remarks above, it should be clear that evolution could be interpreted in ways amenable to ideas of divine design that were central to prevailing understandings of natural theology. American preacher Henry Ward Beecher thus quipped in 1885 that ‘design by wholesale is grander than design by retail’, insinuating that God could use evolutionary processes to bring about his ends and indeed that it was more fitting that he do so. Closer to home, as Lightman has himself shown, in the wake of the publication of the Origin, liberal Anglicans such as Charles Kingsley co-opted evolutionary thought to refashion natural theology.[4] (This approach would become more difficult to sustain when natural selection was fully instated in evolutionary theory in the modern evolutionary synthesis of the twentieth century.) But beyond this, natural theology also continued to thrive in the physical sciences. Hence the devout, Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell could argue that the mutual operations of the laws of nature provided ample evidence of the divine superintendence of the world.[5] Even today, robust design arguments based on the fine-tuning of the physical constant of the universe continue to be articulated. So, yes, Darwin did not precipitate the demise of natural theology as is often supposed.

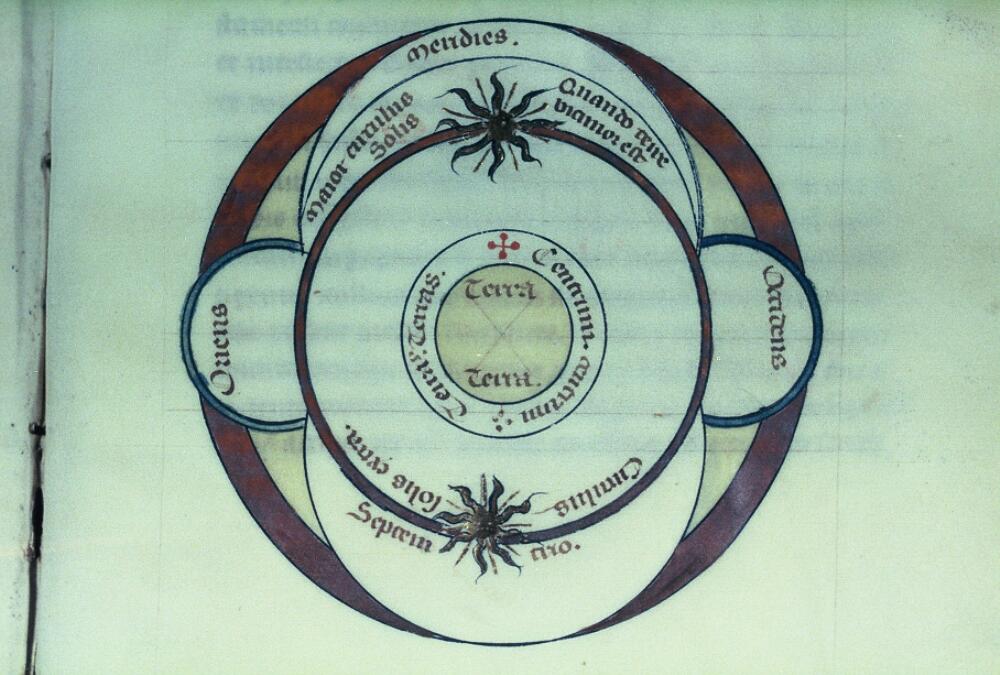

I now turn to the broad historiographical questions about whether Territories sets out a new master narrative, and whether its central thesis is compatible with ‘the complexity thesis’. What John Brooke (along with others such as David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers) had in mind in stressing historical complexity was to contest a dominant narrative in the history of science and religion—the notorious ‘conflict thesis’, which posited an unremitting warfare between science and religion.[6] I am in complete sympathy with efforts to combat the conflict thesis. For none of us does it follow that there were no past tensions between ‘science’ and ‘religion’. It is rather that if we pay close attention to the historical record we find a remarkable range of interactions.[7] The conflict thesis, moreover, was integral to a larger, and equally problematic master-narrative, one that understood Western modernity as the end-point of a teleological historical process in which society progresses from primitive stages of religion and superstition to an advanced stage of scientific rationality. I share with Brooke, and others, the conviction that this is an unhelpful and inaccurate picture of how we come to be where we are today.

Further, my own account of the emergence of the categories ‘science’ and ‘religion’ attempts to provide an explanation for the appearance of historical complexity—a complexity which arises at least partly out of our attempts to project 21st-century conceptions onto a past that carved up the comparable activities in quite different ways. Again, this is a point that Brooke has himself drawn our attention to.[8] What looks to us like complexity, is an effect that arises not only out of the variety of modes of interaction, but also from the fact that the things that are interacting do not map onto our present conceptions of science and religion. In this sense, then, the ‘Peter Principle’ as Lightman designates it, complements the complexity thesis.

Finally, though, The Territories of Science and Religion does seek to promote its own counter-narrative. You will need to read the book to get the full story, but briefly, a key argument is that before the modern period we had no ‘science’ or ‘religion’. Rather, scientia and religio were considered to be internal virtues. In the early modern period these interior qualities came to be objectified, externalized, and reified into practices and bodies of knowledge, giving us our modern categories of science and religion. This process of reification was promoted by a number of factors, among them the demise of Aristotelian understandings of virtue. But, crucially, the coming into existence of these categories was the precondition for any relationship between science and religion, and a key premise for the genesis of the conflict narrative. The story is much more complicated than this, but it is, for all that, a story about the origins of modernity that has about it the look of a narrative, if not a master-narrative.

So, to conclude, I want to put in a good word for narratives and perhaps even master-narratives. Narratives have a place in history, and I am not sure that one can offer a robust or convincing historical account without them. For their part, master-narratives almost inevitably involve over-simplification and presentism. But in spite of their inevitable flaws, such large-scale narratives can be fruitful for the disciplines of history. Witness the way in which even a deeply problematic conflict narrative has galvanized historical research into science and religion for the past three decades. Counterfactually, we might ask how historians of science and religion might have occupied themselves in recent times were it not for the existence of the conflict myth. But myth-busting must eventually come to an end, and perhaps now is the time to start a reconstructive process. The basic plot-line of Territories is an essay in that spirit. I hope it will not only act as a corrective to the manifold inadequacies of the conflict narrative, but also that it might stimulate new questions and new research directions. If Bernie Lightman’s thoughtful remarks offer any indication, it has already achieved some modest success in achieving that goal.

Peter Harrison is the author of The Territories of Science and Religion (Chicago, 2015), an Australian Laureate Fellow and Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Queensland. For more see his Research Profile.

Peter Harrison is the author of The Territories of Science and Religion (Chicago, 2015), an Australian Laureate Fellow and Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Queensland. For more see his Research Profile.

[1] A key work here is Peter J. Bowler, The Non-Darwinian Revolution; Reinterpreting a Historical Myth (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1988). See also the special issue of Journal of the History of Biology 38/1 (2005), on the theme of ‘the Darwinian Revolution’.

[2] Isis 69 (1978), 356-376.

[3] See, e.g., Jerry Coyne, Faith vs Fact: Why Science and Religion are Incompatible (New York: Viking, 2015).

[4] Bernard Lightman, Victorian Popularizers of Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 71-81.

[5] See, e.g., Matthew Stanley, Huxley’s Church and Maxwell’s Demon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), esp. 42-6. More generally, on Lightman’s point, see Jon H. Roberts, ‘The Darwin destroyed Natural Theology’, in Galileo goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion, ed. Ronald L. Numbers (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2009), 161-9.

[6] David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers (eds.), God and Nature: Historical Essays on the Encounter between Christianity and Science (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 10.

[7] John Hedley Brooke, Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), esp. 19-33

[8] Brooke, ‘Science and Theology in the Enlightenment,’ in W. Mark Richardson and Wesley J. Wildman, eds., Religion and Science: History, Method and Dialogue, (London: Routledge, 1996), 23; cf. Brooke, Science and Religion, 6-11.